Overview

Estrogen therapy, with or without a progestogen (progesterone and progestin), has long been prescribed to treat menopausal symptoms. It has been extensively studied, and it is the most consistently effective therapy for vasomotor symptoms. [1, 2] Data from numerous studies suggest that oral, transdermal, or vaginal hormone therapy reduces the severity of hot flashes by 65-90%. [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

Estrogen, a steroid hormone, is derived from the androgenic precursors androstenedione and testosterone by means of aromatization. In order of potency, naturally occurring estrogens are 17 (beta)-estradiol (E2), estrone (E1), and estriol (E3). The synthesis and actions of these estrogens are complex.

In brief, these forms of estrogen can be summarized as follows:

-

Estradiol - Primarily produced by theca and granulosa cells of the ovary; it is the predominant form of estrogen found in premenopausal women

-

Estrone - Formed from estradiol in a reversible reaction; this is the predominant form of circulating estrogen after menopause; estrone is also a product of the peripheral conversion of androstenedione secreted by the adrenal cortex

-

Estriol - The estrogen the placenta secretes during pregnancy; in addition, it is the peripheral metabolite of estradiol and estrone; it is not secreted by the ovary [8]

Table 1 summarizes normal concentrations of the various estrogens.

Table 1. Production and Concentrations of Estrogens in Healthy Women [8] (Open Table in a new window)

Phase |

17b-Estradiol |

Estrone |

Estriol |

|||

Serum Concentration, pg/mL |

Daily Production, mg |

Serum Concentration, pg/mL |

Daily Production, mg |

Serum Concentration, pg/mL |

Daily Production, mg |

|

Follicular |

40-200 |

60-150 |

30-100 |

50-100 |

3-11 |

6-23 |

Preovulatory |

250-500 |

200-400 |

50-200 |

200-350 |

- |

- |

Luteal |

100-150 |

150-300 |

50-115 |

120-250 |

6-16 |

12-30 |

Premenstrual |

40-50 |

50-70 |

15-40 |

30-60 |

- |

- |

Postmenstrual |

< 20 |

5-25 |

15-80 |

30-80 |

3-11 |

5-22 |

Estrogens affect many different systems, organs, and tissues, including the liver, bone, skin, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, breast, uterus, vasculature, and central nervous system (CNS). These effects appear to become most prominent during times of estrogen deficiency, such as the menopausal transition.

Menopausal Transition

Menopause is defined as the permanent cessation of menstrual periods that occurs naturally or that follows surgery, chemotherapy, or irradiation. Natural menopause is recognized after a woman has not had menses for 12 consecutive months and after other pathologic or physiologic (eg, lactation) causes are ruled out. The median age of women undergoing menopause is 52 years. [1]

Symptoms of menopause

During the menopausal transition, a reduction in ovarian function results in a number of symptoms. Symptoms secondary to changes in ovarian hormones can be difficult to distinguish from those due to general aging and/or other medical or endocrine disorders.

Many symptoms are attributed to estrogen deficiency and they vary in intensity among women. Symptoms most commonly reported during the menopausal transition include vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flashes and night sweats, and sleep disturbances. [9]

The prevalence of vasomotor symptoms is 14-51% in premenopausal women, 35-50% in perimenopausal women, a 30-80% in postmenopausal women. [1] Most women have hot flashes for 6 months to 2 years. However, one study group reported that 26% of women had hot flashes for 6-10 years and that 10% had them for more than 10 years. [10]

In 2001, The Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) defined 7 stages of adult women’s lives into 3 broad categories—reproductive, menopausal transition, and post-menopause—with subcategories defined by menstrual cycle data and endocrine studies. In 2011, these criteria were updated and the staging system modified. [11]

In the late reproductive years, menstrual cycles are regular, but menstrual intervals decrease due to decreased luteal phase progesterone and a shorter follicular phase. Endocrine changes include decreased inhibin B and antimüllerian (AMH) levels and a lower antral follicle count in the ovary. While estradiol levels are generally preserved, follicle stimulating hormone levels (FSH) increase slightly. [11] These changes may begin in the early to mid-forties.

During the menopausal transition (perimenopause), menstrual intervals become more variable and FSH also varies or rises. AMH and inhibin B levels remain low. The late phase of menopausal transition occurs 1-3 years before the final menses and is characterized by increased menstrual intervals. FSH levels are greater than or equal to 25 IU/L and AMH, inhibin-B, and antral follicle counts are low.

Following the final menses, menopausal symptoms are most pronounced and coincide with elevated FSH, decreased AMH, and inhibin B and antral follicle counts are very low. Estradiol levels decrease and FSH levels rise higher and then stabilize for the next 3-6 years. Menopausal symptoms most noted are hot flashes (hot flushes). Other symptoms often reported include insomnia, mood changes, and headache.

The first 1-6 years after the final menses is termed “early menopause.” Vasomotor symptoms may begin to decrease but urogenital symptoms and atrophy are more prominent and somatic aging more evident. [11]

Diseases occurring around the time of menopause

Other conditions may mimic the vasomotor symptoms of menopause but may be identified through clinical and laboratory evaluation. [12]

These include the following:

-

Excess thyroid hormone or medullary thyroid cancer

-

Carcinoid syndrome

-

Pheochromocytoma

-

Anxiety disorders

-

Mast cell disorders (usually with gastrointestinal symptoms)

-

Chronic opioid use or withdrawal

-

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

-

Calcium channel blockers

-

Diet - Alcohol, spicy foods, monosodium glutamate, sulfites

-

Medications that block estrogen synthesis or action

-

Chronic infection

Menopause is also the time when the incidence and prevalence of other diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, thromboembolic disease, breast cancer, and osteoporosis, substantially increase. The effect of these conditions becomes important because women live long after menopause, and hormone status directly impacts disease progression and manifestation.

Menopause and Hormone Therapy

Although decreasing estrogen levels alone do not cause all menopausal symptoms, estrogen—with or without progestogen (progesterone, progestin)—has been prescribed for many years to manage menopause. Estrogen was often prescribed to help alleviate symptoms of menopause, as well as to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD) and osteoporosis.

Some have recommended that the term hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in menopause be changed to hormone therapy (HT) or menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), to reflect the shift in focus from replacing hormones to using them for symptomatic relief. [1]

The Clinical Practice Guidelines of the Endocrine Society, 2015, note that for menopausal women < 60 years of age or < 10 years post menopause with bothersome vasomotor symptoms (VMS) (with or without additional symptoms) who do not have a contraindication or excess risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or breast cancer and who are willing to take menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), that estrogen therapy or estrogen and progestin therapy (for women with an intact uterus) be initiated.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved hormone therapy (HT) for four indications: bothersome VMS, prevention of bone loss, genitourinary symptoms, and estrogen deficiency caused by hypogonadism, premature surgical menopause, or premature ovarian insufficiency (POI). This does not encompass the management of POI in young or adolescent women, which requires different management protocols.

Preparations

Several preparations are available for hormone therapy. They include estrogen therapy alone or estrogen in combination with a progestogen (EPT). Unopposed estrogen in patients with an intact uterus increases the likelihood of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma. [13, 14]

Delivery systems

Preparations for estrogen therapy and EPT include oral, transdermal, injectable, and vaginal formulations. Transdermal delivery systems include patches, gels, sprays, and lotions, while vaginal products include suppositories, creams, and rings.

Because of the potential risks and existing controversies regarding high-dose oral regimens, the popularity of low-dose preparations and different delivery systems (eg, transdermal patches, gels, and lotions) is increasing. One vaginal preparation, the estradiol acetate ring, delivers a systemic dose of estradiol lasting for 3 months per ring.

Non-oral preparations avoid a first-pass hepatic effect. Therefore, they may produce fewer changes in lipids, clotting factors, and inflammatory markers. Data have indicated that transdermal preparations, when compared with oral estrogen, are associated with less risk of venous thromboembolism. [15]

EPT may be continuous (ie, daily administration of estrogen and progestogen) or continuous sequential (ie, daily administration of estrogen, with progestogen added on certain days).

See Tables 2-4 for summaries of the available preparations in the United States (adapted from The Endocrine Society). [16] In addition to the preparations listed in the tables, an oral estrogen-testosterone product (Estratest, Estratest HS; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Marietta, GA) is available.

Table 2. Products for Estrogen Therapy (Open Table in a new window)

Oral Products |

|||

Composition |

Product Name |

Available Doses, mg |

|

Conjugated estrogens |

Premarin |

0.3, 0.45, 0.625, 0.9, 1.25 |

|

Synthetic conjugated estrogens |

Cenestin |

0.3, 0.45, 0.625, 0.9, 1.25 |

|

Enjuvia |

0.3, 0.45, 0.625, 1.25 |

||

Esterified estrogens |

Menest |

0.3, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5 |

|

17β-estradiol |

Estrace |

0.5, 1.0, 2.0 |

|

Various generics |

0.5, 1.0, 2.0 |

||

Estradiol acetate |

Femtrace |

0.45, 0.9, 1.8 |

|

Estropipate (formerly piperazine estrone sulfate) |

Ortho-Est |

0.625, 1.25, 2.5 |

|

Ogen |

0.625, 1.25, 2.5 (0.75 mg estropipate = 0.625 mg estrone) |

||

Transdermal and Topical Products |

|||

17β-Estradiol Formulation |

Product Name |

Estradiol Delivery Rate, mg/day |

Frequency |

Matrix patch |

Alora |

0.025, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1 |

Twice weekly |

Climara |

0.025, 0.0375, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1 |

Once weekly |

|

Esclim |

0.025, 0.0375, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1 |

Twice weekly |

|

Menostar |

0.014 |

Once weekly |

|

Vivelle |

0.025, 0.0375, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1 |

Twice weekly |

|

Vivelle-Dot |

0.025, 0.0375, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1 |

Twice weekly |

|

Reservoir patch |

Estraderm |

0.05, 0.1 |

Twice weekly |

Transdermal gel |

EstroGel 0.06% |

0.035 |

Daily, metered pump |

Elestrin 0.06% |

0.0125 |

Daily, metered pump |

|

Divigel 0.1% |

0.003, 0.009, 0.027 (available dose packets 0.25, 0.5, or 1.0g) |

Daily |

|

Topical emulsion |

Estrasorb |

0.05 (3.48g/day) |

Daily |

Transdermal spray |

Evamist (1.7%, metered dose) |

1.53mg/spray |

Initial: 1 spray/day Maintenance: 1-3 spray/day |

Vaginal Products |

|||

Formulation |

Composition |

Product Name |

Dosing |

Cream |

17β-estradiol |

Estrace |

Initial: 2-4g/day for 1-2 wks Maintenance: 1g 1-3 times/wk (1g = 0.1mg estradiol) |

Conjugated estrogens |

Premarin |

Initial: 0.5–2g/day for 1-2 wk Maintenance: 1-3 times/wk (1g = 0.625mg estrogen) |

|

Vaginal ring |

17β-estradiol |

Estring |

Releases 7.5µg/day; 90 days |

Estradiol acetate |

Femring (systemic) |

Releases 0.05mg/day or 0.10mg/day; 90 days |

|

Vaginal tablet |

Estradiol hemihydrate |

Vagifem |

Tab containing 10.3 mcg estradiol hemihydrate = 10 mcg estradiol Initial: 10 mcg tab intravaginally once daily for 2wk Maintenance: 10 mcg tab intravaginally twice/wk (eg, Tues and Fri) |

Table 3. Oral SERM/Estrogen Combination Products (Open Table in a new window)

Oral SERM/Estrogen Combination Products |

||

Composition |

Product Name |

Available Doses, mg |

Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens |

Duavee |

20/0.45 |

Table 4. Progestogens Used for Hormone Therapy (Open Table in a new window)

Route |

Drug, Formulation |

Composition |

Product Name |

Available Doses, mg |

Oral |

Progestin, tablet |

Medroxyprogesterone acetate |

Provera, generics |

2.5, 5, 10 |

Norethindrone |

Micronor, Nor-QD, generics |

0.35 |

||

Norethindrone acetate |

Aygestin, generics |

5 |

||

Norgestrel |

Ovrette |

0.075 |

||

Megestrol acetate |

Megace, generics |

20, 40 |

||

Progesterone, capsule |

Progesterone in peanut oil, micronized |

Prometrium |

100, 200 |

|

Intrauterine |

Progestin, system |

Levonorgestrel |

Mirena |

20 μg/day, 5 y use |

Vaginal |

Progesterone, gel |

Progesterone |

Prochieve 4% |

45 mg/ applicator |

Crinone 4%, 8% |

45 or 90 mg/ applicator |

Table 5. Estrogen–Progestogen Combination Products (Open Table in a new window)

Regimen |

Composition* |

Product Name |

Available Doses & Dosing* |

|

Oral continuous cyclic |

Conjugated estrogens (E) + medroxyprogesterone acetate (P) |

Premphase |

0.625mg E + 2.5 or 5.0mg P, 0.3 or 0.45mg E + 1.5mg P |

|

Oral continuous combined |

Conjugated estrogens (E) + medroxyprogesterone acetate (P) |

Prempro |

0.625mg E + 2.5 or 5.0mg P, 0.3 or 0.45mg E + 1.5mg P |

|

Ethinyl estradiol (E) + norethindrone acetate (P) |

Femhrt |

5µg E + 1mg P, 2.5µg E + 0.5mg P |

||

17β-estradiol (E) + norethindrone acetate (P) |

Activella |

1mg E + 0.5mg P, 0.5mg E + 0.1mg P |

||

17β-estradiol (E) + drospirenone (P) |

Angeliq |

1mg E + 0.5mg P |

||

Oral intermittent combined |

17β-estradiol (E) + norgestimate (P) |

Prefest |

1mg E + 0.09mg P; E alone for 3 days, E + P for 3 days, repeat |

|

Transdermal continuous combined |

17β-estradiol (E) + norethindrone acetate (P) |

Combi-Patch |

0.05mg E + 0.14mg P, 0.05mg E + 0.25mg P |

Twice weekly |

17β-estradiol (E) + levonorgestrel (P) |

Climara Pro |

0.045mg E + 0.015mg P |

Once weekly |

|

* E = estrogen component; P = progesterone component |

||||

Hormone Therapy and Vasomotor Symptoms

As previously mentioned, estrogen therapy, with or without a progestogen, has long been prescribed to treat menopausal symptoms and is the most consistently effective therapy for vasomotor symptoms. [1, 2] Numerous studies suggest that oral, transdermal, or vaginal hormone therapy reduce the severity of hot flashes by 65-90%. [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

In a review by Prior, oral micronized progesterone (OMP) appears to effectively treats vasomotor symptoms and sleep disturbances, and monotherapy (300 mg each night) is potentially safe for symptomatic menopause. [17, 16]

For women with an intact uterus, estrogen should be combined with a progestogen or with bazedoxifene (selective estrogen receptor modulator) to prevent the unopposed adverse effects of estrogen alone on the endometrium.

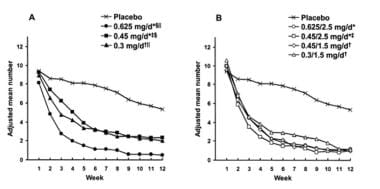

High-dose versus low-dose therapy

Data also indicate that low-dose preparations are effective in reducing the severity and number of hot flashes compared with commonly prescribed doses, though a dose-response relationship may be observed (see the image below). [18] Low-dose estrogen is often considered to be 0.3 mg or less of conjugated estrogen, 0.5 mg or less of oral micronized estradiol, 2.5 μg or less of ethinyl estradiol, or 25 μg or less of transdermal estradiol.

Mean daily number of hot flashes by week for various doses of conjugated estrogen (CEE) alone or combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). (Utian, 2001) A) Placebo and CEE groups; B) Placebo and CEE-MPA groups. Difference vs placebo was significant from weeks *2-12 or †3-12. ‡Difference between CEE 0.45mg/day and CEE 0.45mg/day7 with MPA 2.5mg/day was significant at weeks 3, 4, 5, and 9. §Difference between CEE 0.625 vs 0.45mg/day was significant from weeks 2-12. llDifference between CEE 0.625 and 0.3mg/day was significant at weeks 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, and 12.

Mean daily number of hot flashes by week for various doses of conjugated estrogen (CEE) alone or combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). (Utian, 2001) A) Placebo and CEE groups; B) Placebo and CEE-MPA groups. Difference vs placebo was significant from weeks *2-12 or †3-12. ‡Difference between CEE 0.45mg/day and CEE 0.45mg/day7 with MPA 2.5mg/day was significant at weeks 3, 4, 5, and 9. §Difference between CEE 0.625 vs 0.45mg/day was significant from weeks 2-12. llDifference between CEE 0.625 and 0.3mg/day was significant at weeks 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, and 12.

Differences in symptom response between high- and low-dose preparations tend to be greatest at 4 weeks after the start of hormone therapy and are reduced after 8-12 weeks. Low-dose preparations are desirable because they may be safer than high-dose forms in terms of cardiovascular disease (CVD), venous thromboembolism, stroke, and breast cancer. In addition, they also decrease unacceptable adverse effects, such as irregular bleeding and breast tenderness.

Women who are starting low-dose estrogen therapy should be counseled that it may take 8-12 weeks for their vasomotor symptoms to be relieved. [19, 20] If a low-dose estrogen is selected, a low dose of progestogen can also be prescribed. However, low doses of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (ie, 1.5 mg/day), when combined with low doses of oral conjugated estrogen (0.30-0.45 mg/day), provide adequate endometrial protection. [21] Likewise, a low dose of norethisterone acetate (0.125 mg/day), when combined with estradiol (0.025 mg/day) in a transdermal preparation, also provides endometrial protection. [22]

Furthermore, if low-dose estrogens are used with cyclic progestogen regimens, intervals between progestogen use can be lengthened without significantly compromising endometrial protection. Examples of this approach include using medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg/day for 14 days every 3 months [19] or every 6 months. [23]

The combination product of bazedoxifene, a SERM, with a small dose of conjugated estrogens (CEs) was approved by the FDA in October 2013. Combining a SERM with a low dose of CEE lowers the risk of uterine hyperplasia... This combination significantly reduced the number and severity of hot flashes at weeks 4 and 12 (P< .001). At week 12, bazedoxifene/CEE reduced hot flashes from baseline by 74% (10.3 hot flashes [baseline] vs 2.8) compared with 51% (10.5 vs 5.4) for placebo. [24] Bazedoxifene/CE is FDA-approved for prevention of osteoporosis and treatment of vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women.

The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and The Endocrine Society (ES) suggest a “shared decision-making approach” to decide on the appropriate hormonal dose, route of administration, and to discuss each individual’s risks, treatment goals, and duration of therapy. [12, 16] This updates the concept of “the smallest dose for the shortest length of time” as that may provide insufficient care or even be harmful to some women if HT is curtailed prematurely.

Nonhormonal therapy

Therapeutic options for women who request treatment for VMS but for whom estrogen is not safe or not desired include:

Prescription options that are non-hormonal include the following:

-

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

-

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SERMS)

-

Gabapentin or pregabalin

-

Clonidine (for patients failing gabapentin or pregabalin)

A study by Freeman et al found that the use of escitalopram (10-20 mg/day), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), can be a useful alternative to estrogen/progesterone; escitalopram reduces and alleviates more severe hot flashes. [25]

New approaches under consideration and study include the following:

-

Stellate ganglion block

-

Guided relaxation

-

Hypnosis

-

Cognitive behavior modification

Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in postmenopausal women and menopause increases the risk of CVD independent of patient age.

Results from epidemiologic studies in the 1980s and 1990s, such as the Nurses' Health Study, suggested that hormone therapy was protective against coronary heart disease (CHD) and related mortality. [28, 29] Data from retrospective studies also supported the notion that hormone therapy was cardioprotective. [30] Reappraisal of older studies, such as the WHI, as well as newer investigations consider results and risks associated with the use of HT in younger women (< age 60) or less than 10 years from menopause be separately considered from those of women >age 60 or >10 years from the onset of menopause

For younger women (< age 60 or < 10 years from menopause onset, the effects of E or E+P on initiated less than 10 years from menopause onset lowered the CHD risks in postmenopausal women. It also lowered the risk of stroke and all-cause mortality. An increased risk of VTE was noted. This was most recently upheld by a 2015 Cochrane Review and had first been put forth by an earlier meta-analysis. [31] The WHI, for CEE use alone in younger women with < 10 years since menopause onset showed also less CVD risks except VTE. (A slightly higher risk in women ages 50-59 was present but not statistically significant). [31, 32]

Hormone therapy initiated in older women ( >age 60 ) or greater than 10 years showed a greater risk of CVD as the time since menopause increased. The type of progestin (MPA versus micronized progesterone) could also contribute to a greater CVD risk. No reduction in all-cause mortality was noted. Effects on stroke noted increased risk in older women and variable results in younger women with a lesser risk in lower doses of therapy (oral or transdermal). Patient medical disorders and familial risks of CVD and VTE should also be factored in before implementing HT.

Standard doses of HT resulted in an increased risk of VTE at hormone initiation. This risk could be reduced with lower doses of estrogen or transdermal applications. NO increase in VTE was noted in women using vaginal preparations for genitourinary symptoms.

Therefore, while HT cannot be recommended for cardioprotection, as was formerly touted, the potential risks have been more carefully delineated and will assist calculation of safety in more patients.

Hormone Therapy and Breast Cancer

The association of hormone therapy with breast cancer may have different potential based on estrogen alone, estrogen and a progestin or conjugated estrogen plus bazedoxifene. Different medication formulations and dosages, timing of initiation and length of use may also affect occurrence of malignancy. Individual patient characteristics, combined with medical comorbidities and genetic risk factors and the interactions with hormone therapy are important but not yet clearly elucidated.

While the WHI confirmed an increased risk of breast cancer in users of CEE and MPA, the women in the estrogen (CEE) alone arm had a nonsignificant reduction in breast cancer at 7.2 and 13 years. Smaller trials have also shown a nonsignificant reduction in breast cancer in women taking estrogen alone but observational studies have demonstrated increased risk

There are no RCT for assessing breast cancer in long- term users of estrogen therapy, but one small, randomized, non-blinded trial found no increased breast cancer risk at 10 and 16 years of use (though the trial was addressing cardiovascular risks in recently postmenopausal women using HT. [32] Observational studies and meta-analyses considering risks of breast cancer in women using estrogen for long duration (> 5 years) have shown mixed results

The effects of progestogen therapy with estrogens suggest micronized progesterone (MP) may have less risk on the development of breast cancer than the more potent medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). Randomized trials are needed.

Oral CEE and bazedoxifene prescribed to menopausal women followed for up to 2 years did not show an increased risk of breast cancer

Mammographic breast-density may increase in women taking hormone therapy. Although the biologic importance of this finding has not been established, mammographic abnormalities require additional medical evaluation and may lead to more breast biopsies. [33]

The potential risk of breast cancer in women using HT should be addressed prior to beginning therapy.

Hormone therapy is not recommended for breast cancer survivors. Women who have a family history of breast cancer do not appear to be at increased risk themselves while using HT, nor has increased risk for women post-oophorectomy for BRCA1 or 2 gene mutations been noted. [16] The use of vaginal preparations for genitourinary symptoms is an exception and when used as prescribed does not result in an increase of systemic hormone levels.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause

Breast cancer survivors (BCSs) may suffer genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). This consists of vulvar burning or itching, vaginal dryness or discharge, dyspareunia or post-coital spotting, and recurrent urinary tract infections or symptoms of dysuria, frequency, or urgency. These symptoms may result from menopause related to surgery, chemotherapy, or use of post-treatment medications to reduce risk of recurrence. Genitourinary symptoms frequently arise 1-3 years after the onset of menopause, but some women experience them earlier. BCSs are typically not candidates for conventional menopause therapies (eg, systemic hormonal therapy, vaginal estrogens at standard doses), but nonhormonal vaginal moisturizers or lubricants may have limited use over the long term.

A cohort study by McVicker et al found that vaginal estrogen therapy for GSM did not increase the risk of breast cancer–specific mortality. The study included 49,237 women with breast cancer, and 5% used vaginal estrogen after cancer was diagnosed. [34] A study by Agrawal et al found no increase in the risk of breast cancer recurrence within 5 years in women with a history of breast cancer who used vaginal estrogen therapy for GSM. [35]

Newer management options have become available for all menopausal women experiencing genitourinary symptoms, including the use of adrenal androgen DHEA in vaginal suppository, low-dose/ultra low-dose topical estrogen cream, tablet or vaginal ring, or an oral selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene. Use of these therapies may also reduce the incidence of urinary tract or bladder infections, a cause of significant morbidity in older women. Undiagnosed or untreated urinary infections may lead to urosepsis with an increased risk or long-term morbidity or mortality.

Vaginal laser therapy has been successful for relief of genitourinary symptoms in some women for short periods of time, but the studies available are largely observational short-term, patient self-reports and randomized, controlled trials are lacking. This method of therapy is not FDA approved for genitourinary syndrome of menopause, nor supported by scientific organizations. Early detection and individually tailored treatment is vital for improving quality of life in women with GSM as well as for preventing the exacerbation of symptoms. [36]

Hormone Therapy and Prevention of Bone Loss

Existing evidence largely supports the efficacy of hormone therapy in reducing loss of bone mineral density and decreasing the risk of fracture. [2] The mechanism is via inhibiting osteoclast bone resorption and bone remodeling. A meta-analysis of 22 randomized trials showed a significant reduction of 35% in nonvertebral fractures among women who began hormone therapy before the age of 60 years, with a possible attenuation of the benefit when hormone therapy is started after age 60 years. [37] The WHI investigators also reported significant decreases in the fracture risk with estrogen therapy and EPT. [38, 39] A study by Wang and Sun found that estrogen-only pills, estrogen/progestin combination pills, estrogen-only patches, and combined oral contraceptive pills increased lumbar spine bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. [40]

In fact, all of the systemic hormone therapy preparations (estrogen, estrogen and progestogen and estrogen with bazedoxifene) in standard doses are indicated for the prevention of osteoporosis. Bone mineral density preservation is dose related with less protection of bone at lower doses. Low dose oral (CEE 0.3 mg, estradiol < or=0.5 mg), low dose transdermal estrogens (estradiol patch 0.025mg) and ultralow-dose estrogen transdermal therapy (patch 0.014 mg) have not been shown to reduce fracture risk however but current evidence is limited. The estrogen protection of bone lasts only while in use, and bone density rapidly decreases when discontinued. [16]

The stance adopted by the ACOG is that the use of hormone therapy for osteoporosis prevention or treatment needs to be individualized and needs to include the woman’s need for treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Although other medications are available, such as bisphosphonates and selective estrogen receptor modulators, women with vasomotor symptoms may benefit from hormone therapy. [41] . Women with premature menopause may be better served using combined hormonal contraceptive regimens instead of menopausal hormone therapy when considering preservation of bone density.

The combination product of bazedoxifene, a SERM, and conjugated estrogens (CEs) was approved by the FDA in October 2013. Combining a SERM with CEs lowers the risk of uterine hyperplasia caused by estrogens. This eliminates the need for a progestin and its associated risks (eg, breast cancer, MI, VTE). In clinical trials, this combination decreased bone turnover and bone loss in postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis. Bone mineral density increased significantly more with all bazedoxifene/CE doses compared with placebo at the lumbar spine and total hip and with most bazedoxifene/CE doses compared with raloxifene at the lumbar spine. [42] Bazedoxifene/CE is FDA-approved for prevention of osteoporosis and treatment of vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women.

Hormone Therapy, Cognition, and Quality of Life

Hormone therapy cannot be prescribed for the treatment or prevention of cognitive disorders or dementia.

Cognition

While small clinical trials have shown positive cognition benefits in women after surgical menopause, [43, 44] larger RCT demonstrated neutral findings on cognitive function for women on HT instituted in early menopause. However, in women more distant from menopause (age >65), HT does not improve cognition or memory.

Early institution of HT may decrease the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, while later initiation as noted in four observational studies, may actually increase the risk for Alzheimer’s development. The combined use of CEE and MPA may be detrimental to memory in women with late initiation of HT. [45]

Perimenopausal women may experience improvement of mood on estrogen therapy; other studies report neutral effects. If mood has been improved on HT, the withdrawal of it may prompt recurrence of low mood. [46]

Quality of life

The assessment of HT effects on quality of life most frequently refers to the relief of menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, sleep disturbances or genitourinary symptoms and the improvements achieved are excellent for many women. The relief of symptoms may play a major role in the use of and adherence to hormonal therapy regimens and contribute to motivation for long-term use.

Other Benefits and Risks of Hormone Therapy

The 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of the North American Menopause Society and the 2015 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines suggest other benefits and risks of menopausal hormone therapies—both estrogens alone and estrogen combined with progestogen. Benefits and risks may vary according to patient’s preexisting medical disorders, hormone doses, formulations, and duration of therapy.

Table. Benefits and Risks of Hormone Therapy (Open Table in a new window)

Other Potential Benefits and Hormone Therapy |

Potential Risks of Hormone Therapy |

|---|---|

Improved sleep |

Dry eyes |

Improved retention of skin thickness, elasticity, collagen |

Hearing loss |

Decreased risk of cataracts, open-angle glaucoma |

Olfactory changes |

Improved balance |

Cholelithiasis, cholecystitis |

Improved maintenance of joint health |

|

Improved retention of balance |

|

Possible reduction of colon cancer, type II diabetes |

Hormone Therapy After the WHI

Over the years, the number of prescriptions for hormone therapy has reflected scientific findings. In the 1970s, the number of prescriptions increased to approximately 30 million per year. This practice was likely due to data suggesting the cardioprotective effects of hormone therapy.

In the 1980s, reports of increased rates of endometrial cancer with unopposed estrogen lead to a decrease in annual prescriptions to about 15 million. Then, the addition of progestogen for endometrial protection renewed interest in hormone therapy, and prescriptions again increased.

Between 1995 and 2002, annual prescriptions peaked at about 91 million. Termination of the estrogen-progestin arm of the WHI in July 2002 and release of the HERS II data received considerable media attention and raised serious questions about the safety of hormone therapy in postmenopausal women. Many women stopped taking hormones and began to seek out alternative therapies. Prescriptions for hormone treatment immediately decreased. Of note, prescriptions for vaginal preparations did not change during this time. [47]

The NAMS Hormone Therapy Position Statement in 2012, updated in 2017 with evaluation of new literature and assessment of long-term randomized clinical trials, as well as observational studies reaffirms the use of HT with thorough discussion of risks and benefits and individualization of therapy. Re-evaluation of these risks and benefits over time for each patient allows modifications and/ or continuation of the therapies. [16]

Current Recommendations for Hormone Therapy

The US FDA has approved HT for the following indications:

-

Vasomotor symptoms in menopause. HT is considered first-line therapy for these symptoms unless contraindications exist.

-

Prevention of bone loss and reduction of fractures in post-menopausal women.

-

Treatment of genitourinary symptoms and vulvovaginal atrophy.

The findings of older studies, such as the WHI, do not apply to younger menopausal women who have no other contraindications to HT. The failure to consider and appropriately prescribe HT to younger women with premature or surgical menopause may result in adverse events for them at older ages. [48, 49]

The use of HT for other potential benefits may be instituted following discussion of management options and exclusion of hormone contraindications. Benefits may outweigh risks for women who accept slightly more risks for the benefits.

Reappraisal of hormone dose and delivery route over time in menopausal women allows use of the lowest dose of HT to provide treatment benefits and minimize risks

Bioidentical Hormone Therapy

Bioidentical hormones are plant-derived compounds that have the same chemical and molecular structure as those of hormones produced by the human body. Commercial preparations utilizing “natural compounds” are available– allowing patients the options of therapies biochemically related to a woman’s endogenous estrogen and progesterone. Pharmacy compounded regimens, while allowing some dosage adjustments and combinations not currently available by prescription have not undergone rigorous studies insuring therapeutic equivalence, safety and accuracy and reproducibility similar to commercial preparations. In addition, pharmacy compounded therapies are not usually covered by commercial insurance.

Monitoring of pharmacy compounded therapies are often monitored by saliva hormone levels, and this route of testing and its assays have also not been subject to scientific trials and cannot be compared to serum hormone levels.

Only hormone therapies approved by the US FDA are recommended. This position has been supported and upheld by The Endocrine Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the North American Menopause Society.

Jiang et al compared the safety of compounded hormonal therapy and FDA-approved hormone therapy in postmenopausal women. They found that the incidence of adverse effects was significantly higher in women who received compounded therapy (57.6%) than in those who received FDA-approved therapy (14.8%). [50, 51]

In 2017, an oral soft-gel capsule containing standardized doses of 17-beta- estradiol and natural progestins became available. This product has met FDA safety and efficacy standards. The study of this product was presented in a scientific session of The Endocrine Society at its annual meeting. This provides an option for women seeking a completely “natural” HT regimen to use a safe and carefully regulated medication instead of compounded therapy. [52]

Questions & Answers

Overview

What are the symptoms of estrogen deficiency during menopausal transition?

What are the stages of reproductive aging in women?

Which conditions may mimic the vasomotor symptoms of menopause?

What is the role of estrogen therapy in the treatment of menopausal symptoms?

Which health risks are increased with estrogen therapy?

What are the options for delivery of estrogen therapy?

What is the role of estrogen therapy in the treatment of the vasomotor symptoms of menopause?

What is the efficacy of high-dose versus and low-dose estrogen therapy?

What are the nonhormonal alternatives to estrogen therapy for menopausal symptoms?

What is the role of estrogen therapy in cardiovascular disease prevention?

What is the role of estrogen therapy in the etiology of breast cancer?

How is genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) treated in breast cancer survivors (BCS)?

What is the role of estrogen therapy in bone loss prevention?

What is the role of estrogen therapy in the prevention of cognitive disorders?

How does estrogen therapy affect quality of life?

What are benefits and risks of estrogen therapy?

What is the NAMS Hormone Therapy Position Statement?

What are the FDA approved indications for estrogen therapy?

What is bioidentical estrogen therapy?

-

Mean daily number of hot flashes by week for various doses of conjugated estrogen (CEE) alone or combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). (Utian, 2001) A) Placebo and CEE groups; B) Placebo and CEE-MPA groups. Difference vs placebo was significant from weeks *2-12 or †3-12. ‡Difference between CEE 0.45mg/day and CEE 0.45mg/day7 with MPA 2.5mg/day was significant at weeks 3, 4, 5, and 9. §Difference between CEE 0.625 vs 0.45mg/day was significant from weeks 2-12. llDifference between CEE 0.625 and 0.3mg/day was significant at weeks 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, and 12.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Menopausal Transition

- Menopause and Hormone Therapy

- Hormone Therapy and Vasomotor Symptoms

- Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

- Hormone Therapy and Breast Cancer

- Hormone Therapy and Prevention of Bone Loss

- Hormone Therapy, Cognition, and Quality of Life

- Other Benefits and Risks of Hormone Therapy

- Hormone Therapy After the WHI

- Current Recommendations for Hormone Therapy

- Bioidentical Hormone Therapy

- Questions & Answers

- Show All

- Tables

- References